1

%

of Black women say they have never had an informal interaction with a senior leader.

March is Women’s History month. March 8th marks International Women’s Day. Last month was Black History Month which is an important time to take stock of where we’re at as a society when it comes to levelling the playing field for Black Canadians—and in particular, women.

A historical lens tends to emphasize progress. For example, just 105 years ago, Canadian women obtained the right to vote. On the vast timescale of human civilization, it feels like two minutes ago. So it’s tempting to look at the past century and reflect on how quickly things are moving and how great it all is.

The flaw in this thinking is its implication that progress happens organically, with little actual work to be done. We forget that women’s suffrage was the outcome of years of toil and struggle. Likewise, the progress of Black women in the corporate world has come at great expense and often in the face of great resistance. And it’s by no means settled—that struggle continues to play out in organizations every day.

Why Black Women?

As Lean In’s The State of Black Women in Corporate America describes, “Women are having a worse experience than men. Women of color are having a worse experience than white women. And Black women in particular are having the worst experience of all.”

Put differently, Black women are at a disadvantageous intersection between race and gender. The relative workforce gains made by women are often offset by racial biases that still exist. Put even more bluntly, those women who have climbed the corporate ladder successfully have often benefited from majority

racial status; their battle is confined to sexism. When racism is thrown into the mix, the battle is that much harder—and workforce statistics bear this out:

American Black women hold just 1.4% of C-suite positions and 1.6% of VP roles[1]—despite the fact that Black women request promotions at the same rate as men. In Canada, hiring discrimination is compounded further by Canada’s demographic makeup, where Black women’s minority status is more pronounced than in the US. In a country where Black hiring managers are few, the phenomenon of hiring discrimination—whereby HR managers are more likely to hire someone who “looks like them”—rarely plays out in a Black woman’s favour.[2]

[1] Data cited by Lean In: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey (2018), https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs; LeanIn.Org and McKinsey & Company, Women in the Workplace 2019, unpublished data.

[2] Source: HuffPost, 2019: “Canada Among Top Countries For Racist Hiring In 9 Country Survey”; 2008: “Manager Race and the Race of New Hires”

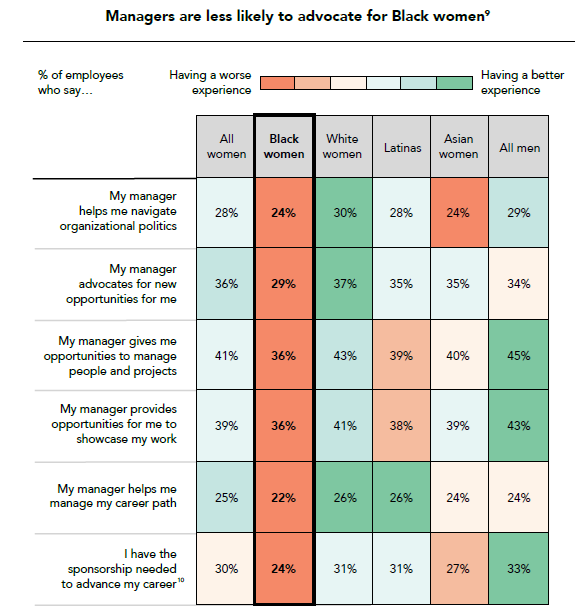

Black women report a lack of support from managers relative to the support received by women of other races and men generally.

In practice, this means their managers are less likely to:

The results are felt in several ways. When a manager isn’t willing to promote a Black woman and her work, that’s a lost avenue on the track to growth and development. Lack of positive feedback and reinforcement can cause an employee to stagnate. When a manager doesn’t nudge an employee toward opportunities, there’s a gatekeeping effect, as the employee may not be sufficiently networked to access those opportunities without a warm introduction. And when a manager withholds challenging projects, the employee is denied the opportunity to prove herself, and build a portfolio she can parlay into greater opportunities. Being confined to less important tasks or projects also contributes to a lack of interaction with senior stakeholders—again, with a resultant gatekeeping effect.

[3] LeanIn.Org and McKinsey & Company, Women in the Workplace 2018.

In Canada, Black women often find themselves in the minority. This has several effects:

No woman is a stranger to microaggressions. Whether it’s a subtle comment on her outfit or light questioning of her judgment in a meeting, gender-based discrimination is a universal experience for women. And Black women report experiencing microaggressions more than twice as often as white women and more than three times as often as men generally.

Microaggressions include comments such as:

Because they are “micro,” microaggressions often get dismissed or ignored, gradually adding discomfort and resentment. When Black women feel continually slighted, their morale may suffer and they may consider resigning. Worse still, they often feel gaslighted when they do call out microaggressions. Others may deny the employee’s experience, tell her she’s imagining things, or accuse her of being oversensitive. Feeding into this phenomenon is the desire on the part of many Black women to avoid being stereotyped as “angry.”[4] Indeed, the myth of the ”angry Black woman” operates much like the “Karen” stereotype that dogs white women—with the net effect that women generally, and Black women especially, stay quiet instead of speaking up.

[4] Daphna Motro, Jonathan Evans, Aleksander P. J. Ellis, and Lehman Benson, “Race and Reactions to Negative Feedback: Examining the Effects of the ‘Angry Black Woman’ Stereotype,” Academy of Management 1 (August 2019), https://journals. aom.org/doi/abs/10.5465/AMBPP.2019.11230abstract

Many women walk a tightrope between being agreeable and being assertive, sensing that an impossibly precise balance is key to their corporate success. If they strive too hard, they’re perceived as nakedly ambitious and described as “cutthroat” or “heartless.” If they behave too agreeably, they invite co-workers and supervisors to take advantage of them—or they end up getting ignored.

For Black women, this effect is magnified. When they flag microaggressions or overt discrimination to their manager, they are fully aware of the potential to start an office fire. In a world where everyone disavows racism, ironically, it can be unwelcome when a Black woman draws attention to it. To walk this ever-more-precarious tightrope, she may end up needing to soothe, reassure, and educate white co-workers who don’t know how to react to a real-life discrimination complaint.

Biases & Stereotypes that Impact Black Women Today

According to MSN, the following biases, stereotypes, and microaggressions impact Black women’s health, educational and economic opportunities, and create barriers that are often ignored.

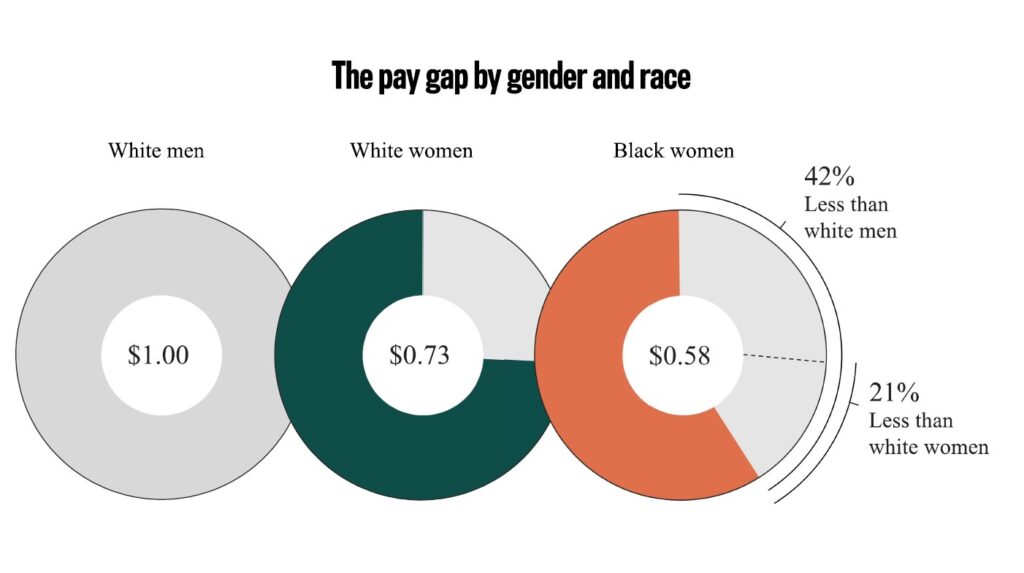

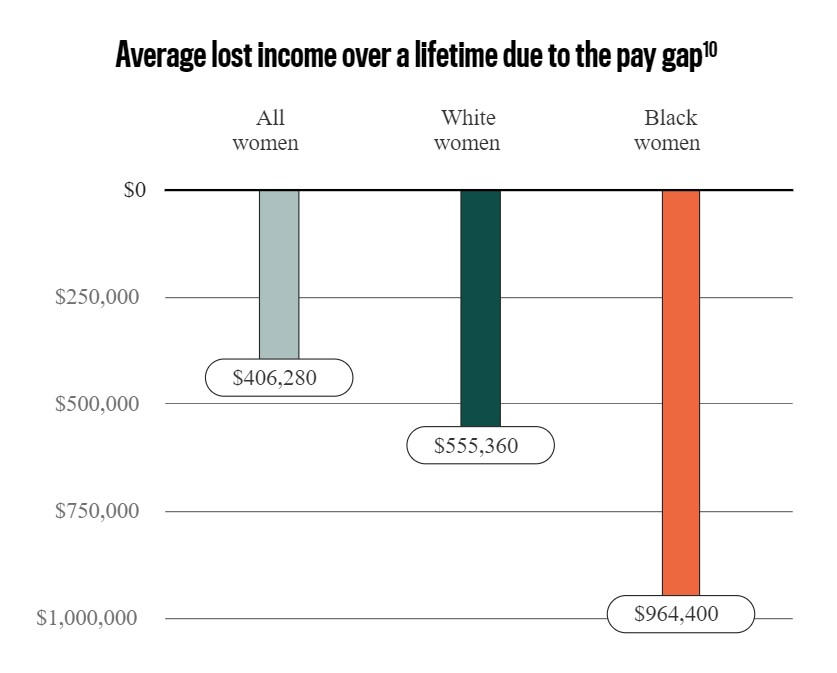

The Pay Gap

Despite the fact that Black Canadians (age 25-54) are more likely to hold a bachelor’s degree or higher (41.1%) than Canadian who are not visible minorities or Indigenous, the pay gap for Black women is significant. According to Lean In, the loss of wages for Black women over their careers can amount to almost one million dollars. Organizations must do more to eliminate the pay gap.

Black Women Aren’t Paid Fairly, Lean In

How Do We Do Better?

History teaches us that progress can happen. The whole point of Black History Month is to draw attention to this—not just the things that have improved, but the work that still needs to be done at individual, social and systemic level.

For Individuals

For individuals, it’s important to take the time to truly understand the experience of Black women. For some people, this is the beginning of a journey. You can find plenty of resources on this site to help you. If you’re not Black, you may be surprised what you learn when you immerse yourself in these materials. Go in with an open mind.

For Businesses

These days, it’s a faux pas not to have a DEI statement on a company website. But as more and more statements pop up, let’s consider what they mean? Do they represent concrete action? Or are they just aspirational? And if they don’t have actions associated with them, how can businesses bring their DEI statements into the real world?

The Lean In report offers some suggestions: